| |

|

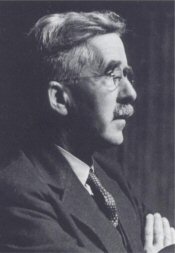

Arthur Mee was born into a working class family

in Stapleford in 1875. He was the second child and oldest son

of Henry Mee, a mechanical engineer, and his wife, Mary. The family

was a very happy one, and in time there were to be ten children

altogether. Both of Arthur’s parents were noted for their

piety, and his father was a deacon in the Baptist Chapel they

attended.

Arthur’s formal education lasted till he was 14 years old.

A friend later wrote that he left school,

... a sound English scholar, but too soon for

even a peep into classical realms. He had no aptitude for chemistry,

mechanics, or geometry, and as an editor he imagined that present-day

pupils might have been equally unattracted by these subjects.

Hence his disinclination to the use in his publications for

the young of technical terms common to most schoolboys of today.

Never would he use such words, for example, as “diameter”

or “circumference,” but always width, and so many

feet or yards round. If a technical term was not familiar to

him, he argued, then it might be unfamiliar to thousands of

others, both adult and juvenile. The practice had its disadvantages

in lack of precision and directness, but Arthur had ever in

mind the one who might not know and might be gravelled by technicalities.

(Ernest Bryant, quoted in Sir John Hammerton’s Child of

Wonder: An Intimate Biography of Arthur Mee, pp. 27-28)

In 1889 he commenced his first job, as a copy-holder for the

Nottingham Evening Post, and this proved to be the first step

to a career in journalism. He was an excellent journalist, and

before many years passed he was in London, first working for one

of the London newspapers, and then free-lancing.

Shortly after his move to London, Arthur Mee married Amy Fratson.

They had one daughter, born in 1901, who they named Marjorie.

Like other children, Marjorie was full of questions, and it was

this fact that led to the publication of The Children’s

Encyclopaedia. Her father later wrote about it as follows:

“...there came into her mind the great

wonder of the Earth. What does the world mean? And why am I

here? Where are all the people who have been and gone? Where

does the rose come from? Who holds the stars up there? What

is it that seems to talk to me when the world is dark and still?

So the questions would come, until the mother of our little

maid was more puzzled than the little maid herself. And as the

questions came, when the mother had thought and thought, and

answered this and answered that until she could answer no more,

she cried out for a book: ‘Oh for a book that will answer

all the questions!’ And this is the book she called for.”

(“To Boys and Girls Everywhere”, in volume 1 of

The Children’s Encyclopedia)

Arthur Mee’s books proved extremely popular with adults

and children alike. His biographer, Sir John Hammerton, comments

“Whatever one’s opinion may be of the merits of Arthur

Mee’s books as contributions to English literature—and

there is room for difference of opinion on that subject—no

one is likely to dispute their inspirational value to their own

age (p. 223f.). According to Hammerton, one of the reasons for

this popularity was that “[he] had the power to make plain

to the average man, woman, and child the aspects and imports of

the problems which the very men who had wrested them from nature

could not make so plain” (p. 158) – and this was done

in such a way as to communicate the writer’s own enthusiasm

for his topic to the reader. There are scientists and historians

today who credit Arthur Mee with introducing them to the subject

that later became their specialty. Others tell of how they taught

themselves to read with the aid of the Children’s Encyclopedia,

or how they read it from cover to cover, with obvious delight.

He was a prolific writer. Apart from The Children’s Encyclopedia

he produced a number of biographies, a Children’s Bible,

Children’s Shakespeare, books of travels around England

and Europe, and various anthologies of quotations from great men

and women of the past (his Book of Everlasting Things, for instance).

He also founded and edited the Children’s Newspaper, and

was dubbed “journalist in chief to British youth”.

Finally, it must be said that Arthur Mee was a man of his time.

He was known publicly as a Christian, and stood up boldly for Christian

principles, though at the same time he was a staunch believer in

evolution, and seems not to have believed in the literal resurrection

of the Lord Jesus. His view of evolution was like that of Charlotte

Mason (among others) – namely that evolution was a wonderful

discovery whereby people could now see, scientifically, exactly

how God had created the world. He had a great reverence for the

Bible and its teachings, and this comes across very clearly in what

he writes. His writings also reflect his intense patriotism and

his optimism that the world was getting better, and would continue

to do so for the rising generation. Arthur Mee died suddenly in

May 1943, following an operation.

Copyright © Ruth Marshall

2004 http://wonder.riverwillow.com.au

Further information on Arthur Mee's life and work may be found in:

Sir. John Alexander Hammerton, Child of Wonder: An intimate biography

of Arthur Mee, Hodder & Stoughton: London, 1946 [out of print]

Simon Appleyard, The Storytellers: A Glimpse into the Lives of 12

English Writers, First published in 1991 by This England Books,

73 Rodney Road, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, ISBN 0 906324 20 3

[available from This England]

|